Research

Biodiversity and Conservation in the Sea of Cortez (Gulf of California)

The accumulation of species diversity since the Gulf’s opening ~6 million years ago has produced one of the most biologically rich marine regions on earth. The coastlines, offshore benthic regions, and pelagic waters of the Gulf are famous for supporting not only an extraordinary biological diversity but also exceptionally high productivity and large populations of marine taxa: invertebrates, fishes, cetaceans, sea turtles, and birds. Its 6000+ recorded animal species is estimated to represent about 70 percent of the actual (total) faunal diversity lurking in its rich waters. So productive are the Gulf’s waters that over half of Mexico’s total fisheries production comes from this region. However, this biodiversity is threatened. Much of the Sonora-Sinaloa coast has been heavily impacted by “development” (urbanization, marina construction, coastal agriculture and aquaculture, etc.) and by over-collecting of marine life by both residents and tourists. The Sonora-Sinaloa coastline now harbors but a pale shadow of its former diversity. It is human nature for tourists to pick up creatures found along the shore and to take them as souvenirs, but every time this happens a piece of the food web disappears, and today millions of souvenir seekers carry away tidepool animals every year. Also of critical concern is the continued use of industrial shrimp trawls that destroy the benthos and, in the Northern Gulf, annually capture thousands of juvenile totoaba. Also of concern is the impact of poorly regulated shrimp farm development in or adjacent to wetlands in Sonora, Sinaloa, and Nayarit. Over-fishing and use of long-lines and gillnets are also extracting huge numbers of fish, seabirds, turtles, and marine mammals from the waters of the Gulf. In the Northern Gulf, illegal gillnetting of totoaba (for their swim bladders, for the Chinese market) is driving the endangered vaquita porpoise to extinction. However, the islands and the Baja California Peninsula have fared better and these remain strongholds of biological diversity. Aside from poor fisheries management, the Northern Gulf continues to sustain a high productivity and relatively healthy ecosystem. However, I have worked in the Sea of Cortez for nearly 50 years and the changes I have seen have been dramatic. I continue to undertake research and work with non-profits, government agencies, and UNESCO in Mexico to help the conservation movement that is now making serious advances to protect the Sea of Cortez. For my own research papers on this subject see the “Papers” page on this website, for a bibliography of key papers/books on the Sea of Cortez (periodically updated), click here pdf. For a history of name use for the Gulf of California, click here Names for Sea of Cortez.pdf. To access the Macrofauna Golfo on-line invertebrate database, click here. FOR MORE INFORMATION ON THE SEA OF CORTEZ, click here.

I currently have three active research programs:

• Biodiversity and Conservation in the Sea of Cortez (Gulf of California)

-

• Biodiversity and Biogeography in Arizona’s Sky Islands

-

• Cultural Anthropology of Pimería Alta and Mesoamerica

Estero Soldado (Sonora) is one of the best preserved mangrove lagoons in Sea of Cortez

Yellow-crowned night-herons, brown pelicans, and oystercatchers are common shorebirds

in the Sea of Cortez

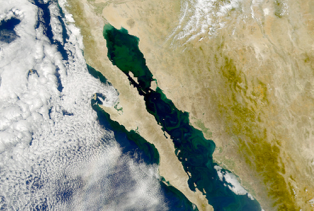

NASA images: Phytoplankton blooms in the Sea of cortez and the Pinacate Volcanic Field and Gran Desierto

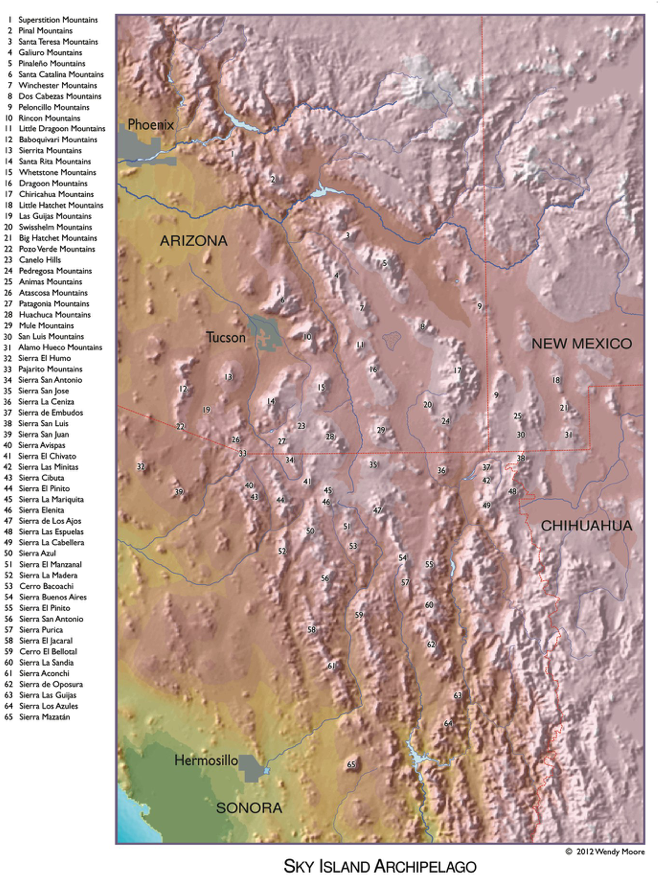

Biodiversity and Biogeography of Arizona’s Sky Islands

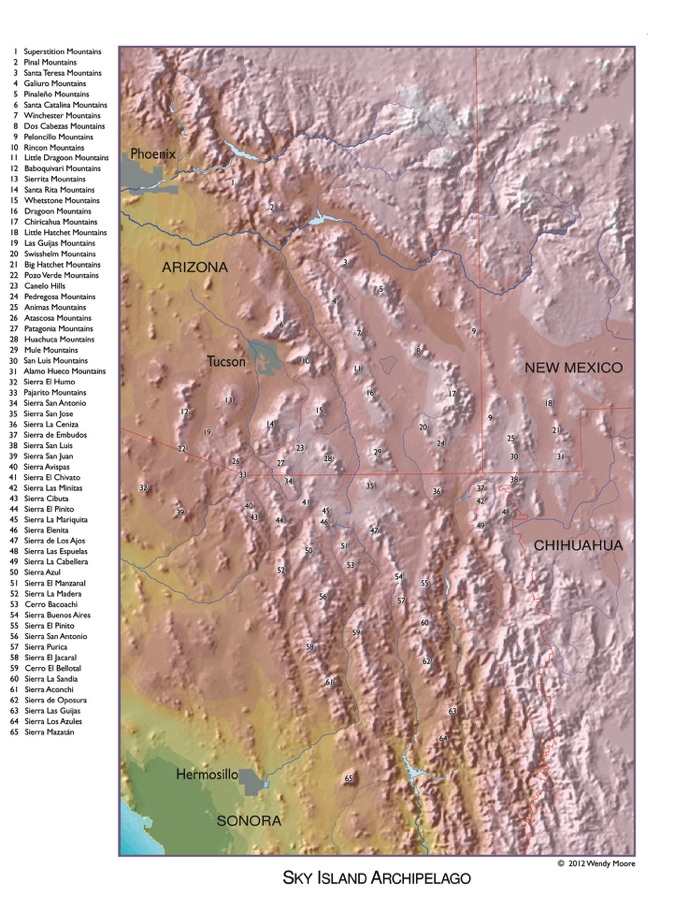

The outcome of millions of years of mountain building, the 7250 km (4500-mile) long North American Cordillera (or “Western Cordillera”) runs from northern Alaska to southern Mexico. This great cordillera, the spine of the North American continent, has but one break, a low saddle between the Rocky Mountains/Colorado Plateau and the Sierra Madre Occidental, which forms a biogeographic barrier between the montane biotas of temperate and tropical North America. The Madrean Sky Islands are the ~65 isolated mountain ranges that span this Cordilleran Gap. Sometimes called the “Sky Island Archipelago” or “Madrean Archipelago,” these mountain ranges are a unique subset of the Basin and Range Province and cover about 45,000 sq mi (~20,000 sq mi in the United States). As a cooperator on Dr. Wendy Moore’s Arizona Sky Island Arthropod Project (ASAP: www.moorearthropods.com), University of Arizona, Rick Brusca is helping the Moore team explore and document ground-dwelling arthropod biodiversity and biogeography in the Madrean Sky Islands north of the U.S.-Mexico border. ASAP is a new research program that combines systematics, biogeography, ecology, and population genetics to study ground-dwelling arthropod diversity, abundance, distribution and community structure along elevation gradients and among mountain ranges in the Desert Southwest. Ground-dwelling arthropods represent taxonomically and ecologically diverse organisms that drive key ecosystem processes. Using data from museum specimens and material collected from long-term pitfall trap monitoring, ASAP will document diversity patterns across the Sky Islands to identify patterns of endemism, phylogeography, and the evolutionary origins of arthropods in these “island communities.” In addition, ASAP will make use of the natural laboratory provided by the Sky Islands to evaluate the ecological roles of arthropods across elevational and environmental gradients on the mountains. Baseline data will be used to determine climatic boundaries for target species, which will then be integrated with climatological models to predict future changes in arthropod communities and distributions in the wake of rapid climate change. As part of this project, we have developed field keys to Conifers of Southern Arizona (Key to So. AZ Conifers.pdf) and Oaks of Southern Arizona (Key to So. AZ Oaks.pdf). Preliminary results of the ASAP project were presented at the Madrean Sky Islands Conference (http://www.madreanconference.org/), May 2012, and were published in the compendium volume from that meeting (Moore et al 2013.pdf). An analysis of montane plant distributions in the Santa Catalinas was published in 2013 Brusca et al. 2013 Catalinas.pdf. An analysis of arthropod distributions in the Santa Catalinas was pubished in 2015 Meyer et al 2015 Arthropods of Catalinas.pdf. For further information on the ASAP project, contact Dr. Wendy Moore (wmoore@email.arizona.edu).

FOR MORE INFORMATION ON ARIZONA’S SKY ISLANDS Click Here.

The Santa Catalina Mountains, seen from the Tucson Valley

The Galiuro Mountains, beyond the San Pedro River Valley. The snow-capped Mt. Graham (Pinaleño Mountains) can be seen peaking over the top of the Galiuros

Hoodoos in the Santa Catalina Mountains

Border pinyon pine (Pinus discolor) is the characteristic pinyon of the border area of the Sky Island Region.

The Santa Rita Mountains,

Arizona

Cerro el Bellotal,

near Arizpe, Sonora

Chiricahua Mountains,

Arizona

Cultural Anthropology in the Pimería Alta and Mesoamerica

Since 2004 I have worked with a team of other anthropologists and archaeologists to conduct surveys and excavations along the coast of northwest Sonora (Mexico). In 2020 we published a summary of our collective findings (Mitchell et al 2020 Upper Gulf archaeology.pdf), and in 2024 we published a large contributed volume on our research program (Mitchell et al. 2024, U.A. Archaeological Research Papers No. 83). One of our key findings is strong evidence supporting the hypothesis that the roots of the O’odham People can be seen in a coastal foraging culture in northern Sonora at least 6,000 years before present. This hypothesis also is supported by a large genetic study of Southwestern Native Americans (Nakatsuka et al. 2023). The implication is that the O’odham are the oldest and most widespread indigenous people living in the southwestern U.S. and northwestern Sonora. Furthermore, the O’odham have no cultural, genealogical, or genetic relationship to the Hohokam culture (e.g., Brusca 2025 Hohokam & O'odham.pdf). My interests in Mesoamerican anthropology began in the 1980s, when I undertook extensive travel in southern Mexico, Guatemala, and adjacent countries. These studies are expressed in both published research (e.g., Vidal & Brusca 2020 Biocultural Diversity in Mexico.pdf) and in two award-winning historical novels on the Maya (In the Land of the Feathered Serpent) and the Aztecs (The Time Travelers).

Two views of the Pinacate Mountains, northwest Sonora. The view across the town of Puerto Peñasco shows the southeastern extent of the Gran Desierto sand sea wrapping around the side of El Pinacate. The view from space shows the entire Pinacate lava field and much of the Gran Desierto. The large Bahía Adair is in the lower left of the image, and to the right of that is the coastal town of Puerto Peñasco and nearby Estero Morua (site of much of my archaeological/anthropological work). The track of the ancient Río Sonoyta can be seen running all the way to the coast (visible due to vegetation in the riverbed, surviving on the river’s underground flow). This entire coastline was inhabited more-or-less continuously since at least 4,000 BC by hunter-gatherers that were predecessors of today’s O’odham People. Freshwater springs occur at the head of the Gulf (e.g., El Doctor and El Tornillal, near the town of El Golfo de Santa Clara) and along the shore of Bahía Adair.

Two freshwater springs at Salina Grande, at the northwest side of Bahía Adair. For thousands of years these sites were sources of fresh water and salt for ancient and modern O’odham People.

Bahía Cholla, a small embayment at the southeastern edge of Bahía Adair, maintains healthy populations of the same molluscs harvested by prehistoric people along the northwest coast of Sonora (Brusca 2024 Ecology of NE Gulf.PDF). The shells of these molluscs form massive “kitchen middens” all along the shoreline that, along with various archaeological artifacts, are a record of past inhabitation (photo on right). The range in the background is locally known as “Black Mountain.”

Middens at Estero Morua (near Puerto Peñasco) are dense and deep, and cover many kilometers around the estuary. These photos show some potsherds and a pendant recovered at this site.