Cool Inverts

Enjoy the wonderful world of invertebrates, which comprise 95 percent of all living animal species. Featured invertebrates on this page will change as time allows.

Crustaceans that Replace Organs

The crustacean order Isopoda (the pillbugs, sowbugs, gribbles, etc.) includes ~10,000 described living species, split more-or-less evenly between terrestrial/freshwater and marine environments. The largest species live in the sea, where they can reach ~2.5 ft in length (Bathynomus). One of the largest isopod families is Cymothoidae, which are ectoparasites on marine and freshwater fishes around the world. Cymothoid mouth parts are specialized to “suck” blood from their host fish. Some cymothoids live on or under (encapsulated) the skin, whereas others inhabit the gill chamber or mouth. All are protandric hermaphrodites, developing first as males and then changing sex to become females. One of the most unusual cymothoid species is Cymothoa exigua that, in the Gulf of California, parasitizes a range of fishes, one of which is the spotted rose snapper Lutjanus guttatus. Uniquely, the isopod drains so much blood from the snapper’s tongue while feeding, that the tongue degenerates and disappears. (The tongue in fishes is little more than an extension of the basihyal bone.) This isopod remains attached to the muscular tongue stub with its hooklike legs, and the snapper then utilizes it as a “replacement tongue,” apparently continuing to feed and respire normally. This phenomenon appears to be the only known example (in animals) of a functional replacement of a host structure by a parasite. In 2013 a second occurrence of this phenomenon was documented from the Indian Ocean, where the parasite species is Cymothoa borbonica and the host fish the large-spot pompano Trachinotus botla (although there have been several erroneous reports from other species and localities in the world). Brusca & Gilligan 1983 Tongue Replacement.pdf

Swimming jellies photographed at the Monterey Bay Aquarium, June 2018. Left to right: Aurelia labiata (Scyphozoa), Chrysaora fuscescens (Scyphozoa), Hormiphora (Ctenophora). In scyphozoans, contractions of the coronal muscles produce rhythmic pulsations of the bell, driving water out from beneath the subumbrella and moving the animal by jet propulsion. The stiffened cellular collenchyme includes elastic fibers that provide the antagonistic force to restore the bell shape between contractions. In ctenophores, the beating of the ctenes, arranged in comb rows, provides most of the locomotor power that allows the animals to move up and down in the water. Each comb row comprises many ctenes, and each ctene consists of a transverse band of hundreds of very long, partly fused cilia that beat together as a unit. Ctenophores are the largest animals known to use cilia for locomotion. The beating comb rows appear iridescent, probably caused by the dense and highly regular packing of ciliary elements at the base of each comb row.

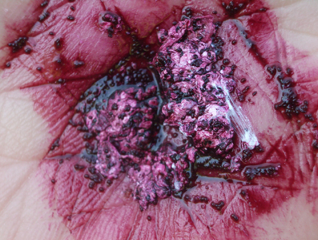

Beetles with Worms

Over 25,000 species of nematodes (roundworms, threadworms) have been described, and they comprise one of the most abundant groups of animals on earth. One study found over 90,000 individuals in a single rotting apple, and good farmland typically harbors 3 to 9 billion nematodes per acre. Many nematodes are parasitic, and they infest nearly every kind of living organism, including insects. These long nematodes (family Mermithidae) are larvae that emerged from an infested carabid beetle (Metrius contractus) from California. The worms are so long they had to coil themselves up to fit inside their host! Mermithids are primarily arthropod endoparasites, although some species have been recorded from annelid worms and molluscs. Thanks to Wendy Moore for the photos and Patricia Stock for the worm ID.

Bryozoans in Oceans and Rivers

Bryozoa (=Ectoprocta) comprise a diverse phylum of about 4500 described living species, all of which grow as tiny individuals forming colonies encased in a soft or hard exoskeleton. Common in shallow marine environments, uncommon in freshwater habitats, most people don’t even notice the sessile, attached colonies of these creatures. Shown here is the beautiful purple Disporella, common intertidally throughout much of the eastern Pacific, and two freshwater species from the Willamette River (Plumatella emarginata and P. fungosa, left/right). Thanks to Stan Gregory for the Willamette River Plumatella photo.

Rabbits in the Sea

Sea hares are common intertidal slugs (“shell-less” molluscs) found throughout the world’s seas. They spend their time slowly crawling over the seafloor grazing primarily on seaweeds. Here you see a specimen of the eastern Pacific Aplysia californica just beginning to release its store of purple ink, a characteristic defense behavior. Sea hares are prolific breeders, their yellow spaghetti-like egg mass containing millions of eggs. The simple nervous system and large size of sea hares have made them a favorite research organism for neurobiologists. Aplysia californica grows to lengths of 30 inches (fully extended). Aplysia vaccaria, in the Sea of Cortez, grows to a whopping 45 inches--that’s one big slug!

Who’s Been Spitting in my Garden

Spittle bugs are assigned to several families of true bugs (order Hemiptera), one of the largest insect orders with about 85,000 described living species. In three spittlebug families, the nymph stage produces a cover of frothed-up plant sap (the excess filtered liquids from feeding on its host plant) resembling spit—hence the common name. The froth hides the nymphs from predators, provides some temperature control, and also keeps the animals moist.

What are those White Blobs on my Cactus

Common in the Southwest, cochineal are scale insects (Coccoidea: Dactylopiidae) that resemble mealybugs and live on prickly pear cactus (Opuntia). They cover themselves with white waxy plates for protection from the sun and predators. Cochineal are cultivated on Opuntia pads in Mexico for their crimson dye, which can be seen by crushing some of the bugs in your hand. The dye was replaced by aniline dyes years ago for fabrics, but it is still used as an FDA-approved source of red food dye. Females are wormlike; males more buglike.

Sponges—Primitive but “Clever”

Sponges, the phylum Porifera, are the most primitive living animals. They lack true embryological germ tissue layering and, as adults, do not have true body tissues or organs. Instead, their cells are totipotent, capable of changing form and function as needed. In many ways, they function like protists, or unicellular animals. About 5500 living species of sponges have so far been described. Most are marine, but a few species are freshwater. The photo of bath sponges for sale at a street market in Provence (France) reminds us that some sponges have no mineralized skeleton at all. Bath sponges (Spongia, Hippospongia) have been harvested for millennia; Homer and other ancient Greek writers mentioned an active Mediterranean sponge trade nearly 3000 years ago. At the opposite end of the spectrum from benign bath sponges are the boring sponges, which secrete acids to bore holes into calcareous structures throughout the world’s oceans (e.g., mollusc shells, coral skeletons). Shown here is the beta stage of Cliona californica and the results of its boring action on a clam shell. This common tropical eastern Pacific species has a most remarkable life history, beginning with larvae that settle out on a shell or other calcareous object, and immediately begin to bore. The alpha stage is wholly boring and usually not seen, living inside its host structure. At some point, the sponge erupts from the host as a beta stage (shown in this photograph). Later in life, the sponge breaks free altogether to become free-living, often becoming unattached and rolling in and out with the tides. The beta and gamma stage used to be considered a different species (Pseudosuberites pseudos) but these were recently discovered to be the same animal as Cliona californica.

Not Quite Giant Squids

The large phylum Mollusca (~100,000 described living species) contains a great variety of animal forms, from snails and clams, to tusk shells, octopuses, and squids—the latter have long held the fascination of humans. Especially captivating have been the “giant squids” (several species in the genus Architeuthis), the largest of which has been measured at 43 feet in length (body + longest tentacles). However, even this is bested by the “colossal squid” (Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni), which has been measured at 46 feet in length—the largest living invertebrate. Not quite in the same category sizewise, but still exciting to see and wonderful to eat, is the eastern Pacific “jumbo squid,” Dosidicus gigas, also known as the “Humboldt squid.” Shown here is a jumbo squid held by Alex Kerstitch, with the beak and pen of this species. Jumbo squid reach 100 lbs or so and are known to attack humans (divers)—in fact, Alex was attacked when diving in the Sea of Cortez! In 1974 a fishery began for this squid in the Sea of Cortez (Gulf of California), and it has since grown to major importance.

Not Only in the Sky are there Stars

Around 7000 species of living Echinoderms have so-far been described. Two-thousand of these belong to the class Ophiuroidea, the brittle stars and basket stars (many-armed brittle stars). Ophiuroids are utterly unique in their arm anatomy. In this group, the coelom (body cavity) of the arms is nearly obliterated by the presence of huge, articulating, skeletal vertebrae. The vertebrae are nearly perfect analogs of the spinal vertebrae see in the chordate subphylum Vertebrata (e.g., mammals, birds, reptiles, fishes, etc.), articulating similarly and functioning for the same purposes—an exceptional case of convergent evolution. In this dissection, the large “jaws” of the central disk are also apparent, comprising a complex and uniquely echinoderm structure known as Aristotle’s Lantern. Shown are three ophiuroids from the Sea of Cortez: Ophionereis annulata, Astrocaneum spinosum, and the skeleton of Ophioderma panamense.

Cucumbers in the Sea

Sea cucumbers (class Holothuroidea) are some of the strangest echinoderms in the sea—and strangest invertebrates on earth. Their bodies are fleshy, sausage-shaped sacks filled with coelomic fluid, which is mostly sea water, and the whole thing is one big hydraulic system in which muscles of the body wall contract and relax in various ways to change the shape (and size) of the animals. Many species can contract and expand their body ten-fold in length, or more. Most are relatively sedentary, living on the ocean floor and capturing food from the sediment or the water with a set of tentacles that surround the mouth. However, a few species are pelagic and live in the open water of the world’s seas. Most sea cucumbers respire by pumping sea water in-and-out of their anus, where gas-exchange takes place in outgrowths of the gut (called “respiratory trees”) that penetrate into the body coelom. Also attached to the gut in many species are Cuverian tubules—extremely sticky defense structures that are used to entangle attacking predators by forcibly eviscerating them (along with most of the gut) out the anus or a rupture in the body wall. All these vital body parts are quickly regenerated by the cucumber. Shown here are three species from the Sea of Cortez: Isostichopus fuscus, Holothuria inhabilis (highly contracted), and Euapta godeffroyi. The last is a snakelike species that can grow from a contracted length of around six inches, to an expanded length of four feet!

Sally Lightfoot

Certainly one the most famous crabs in the New World, Sally Lightfoot (Grapsus grapsus) gained everlasting fame with John Steinbeck’s prose (in The Log from the Sea of Cortez) when he wrote: “They seem to be able to run in any of four directions; but more than this, perhaps because of their rapid reaction time, they appear to read the mind of their hunter. They escape the long-handled net, anticipating from what direction it is coming. If you walk slowly, they move slowly ahead of you in droves. If you hurry, they hurry. When you plunge at them, they seem to disappear in little puffs of blue smoke......It is impossible to creep up on them. Man reacts peculiarly but consistently in his relationship with Sally Lightfoot. His tendency eventually is to scream curses, to hurl himself at them, and to come up foaming with rage and bruised all over his chest.” Widely distributed in tropical and subtropical America and Africa, including in the central and southern Sea of Cortez. In the Galapagos Islands, they are known to feed on ticks of the marine iguana.